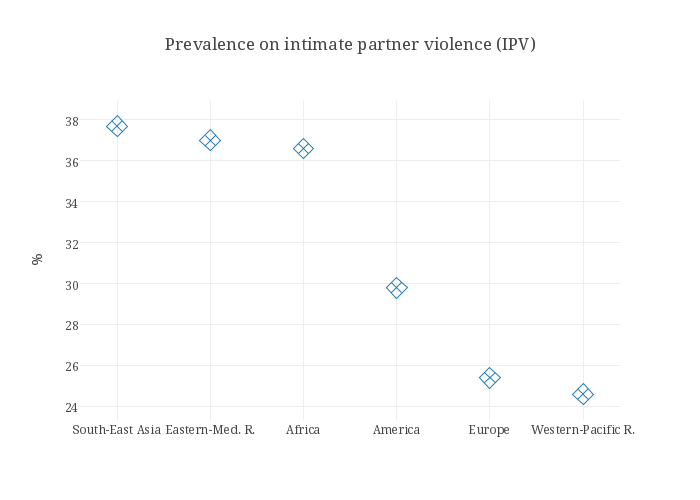

In the European Region, one in four women has been a victim of physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner in her lifetime, and one in ten has experienced non-partner violence. Violence between partners is endemic and widespread, but for immigrant women it is even worse, especially because of the conditions in which they often live in the host country.

In Spain, for instance, a cross-sectional study published in 2012 showed an intimate partner violence (IPV) prevalence of 27.9 percent in migrants, compared to 14.3 percent in Spanish women. But it is certainly not the only example. 43 percent of Roma women experienced physical violence and 36 percent suffered from psychological violence. At the same time, official data on IPV among ethnic minority women are often lacking, due to huge barriers that preclude immigrant women to report episodes of gender inequality.

This is a widespread issue, as underlined by Ban Ki-Moon, UN Secretary General, during the International Migrants Day, on 18th December: “Women and children, always the most vulnerable among the vulnerable people, suffer most […] all migrants should have access to essential health services”.

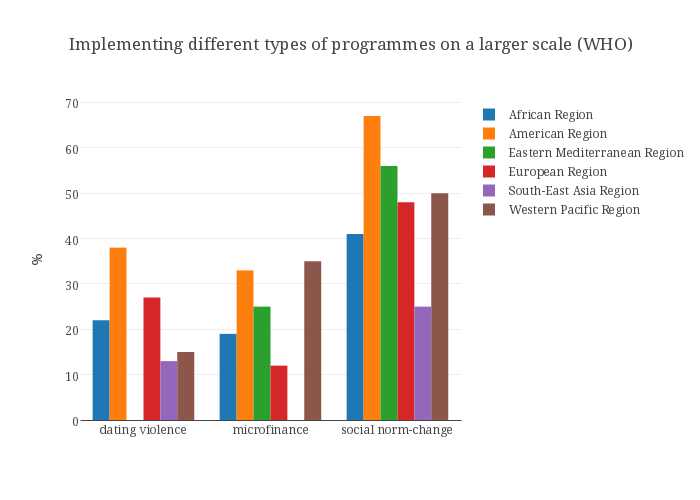

In this sense, institutions have the most important power. Firstly, concerning the monitoring of this problem at national level, secondly because it is important to pass the message that violence against women is preventable. The most recent report concerning this issue has been published in 2014 by WHO and it titled Preventing and addressing intimate partner violence against migrant and ethnic minority women: the role of the health sector. The report aims to provide input into the role of the health sector in preventing and addressing IPV among migrant women and those of ethnic minorities.

This last publication is a policy brief, so its crucial point is to describe the problem in order to find a solution, through a series of recommendations for health policy and health systems, health facilities and health service providers. Because IPV can be prevented only if all institutions – meaning Governments, NGOs, but also associations – collaborate.

An interesting map concerning the active surveys on violence against women comes from another WHO report, published in December 2014, called Global status report on violence prevention in 2014 and focuses on all kind of violence throughout the World. Data on partner violence reveal that the majority of countries around the world has some form of monitoring concerning this topic, even for instance some of the poorest countries worldwide, where fundamental human rights are not guaranteed. The problem is that it does not seem a good indicator for the real IPV situation. In fact, according to WHO data, in 2010 lifetime IPV was, for instance, at 16.3 percent in East Asia and 65.64 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Monitoring is just the first step. Institutions must then coordinate themselves and act. One of the first paths is to improve the accessibility of migrant women to the health system.

As the report shows, the underuse of health services among women experiencing IPV is mainly related to a lack of knowledge about national women’s support programmes in the host country. Moreover, language and cultural differences could also create misunderstanding between these women and the health staff, which often is not able to provide the right degree of confidence. In other words: the importance of communication among the stakeholders and between migrants and the health care providers.

Actually, an effective answer requires a multi-level approach. There are three different levels on which Institution can act: at the health policy and health system levels, at the health facility level and finally at the health provider level. Let's start with the first, whose main points are to promote social participation in the organization of the whole health policy and the coordination between the health system and other sectors, to identify specific objectives and indicators for monitoring, and to evaluate the national scenario.

At the health facility level, the main recommendations concern barriers that keep migrant and ethnic minority women from accessing to health services. For OMS the best way to achieve this goal is by identifying relevant programme adaptations that respond to the health needs of these groups of people, by developing systems for organizational learning relating to intimate partner violence and by exploring opportunities for prevention activities within primary care.

Finally, the health provider level, which means working face to face with women who are in a very vulnerable condition. At this level, the most important thing is to create networks of health care professionals, in order to build a reference system for ethnic minority women. But there is another problem concerning IPT: health care providers often lack many cultural information about these ethnic groups, while at the same time migrants do not know many legal aspects, like the legal implications of health service work with regard to intimate partner violence. Moreover, is fundamental for health provider to become familiar with research literature on health provider bias and discrimination in medical decision-making.

To sum up, the WHO main message is that violence can be prevented, but it does not mean that this is an easy goal to achieve, especially in ethnic minority communities. However, there are some good practices already working in Europe, and the WHO report shows three of these case studies. The first is RIU VIOLETA (2010), a community-based intervention that aims to promote gender equality and prevent GBV especially in Roma and migrant communities. The intervention was supported by the Health Council of the Valencia autonomous community government and the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality. Another example of good practice is a special toolkit developed in 2009 in UK to enable a better care of Asian women with physical and mental health consequences of living with domestic violence and abuse. Finally, between 2010 and 2011, a French NGO offered migrants people some professional training courses on violence against women and girls.