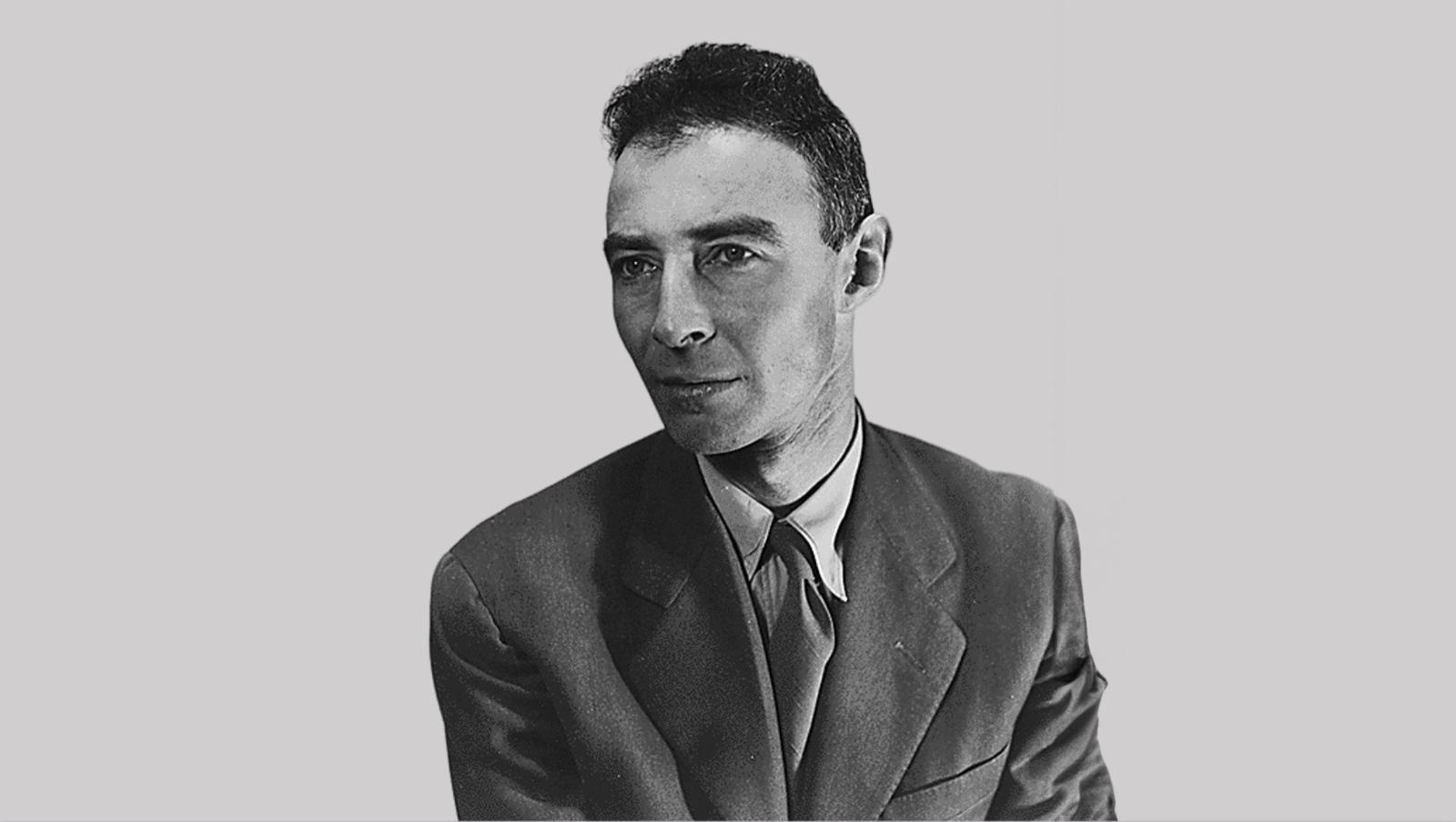

The story of the physicist Robert Oppenheimer is a controversial one, filled with both highlights and shadows. Although it has already been the subject of numerous biographies, it is now the focus of the eponymous film directed by Christopher Nolan. Fabio Terragni reviews it for 'Scienza in rete'.

It's true: Robert Oppenheimer didn't "invent" the atomic bomb. The most tragic achievement of 20th-century science and technology was the result of the first example of Big Science: the Manhattan Project, an unprecedented effort by the American government to outpace Nazi Germany, which cost over two billion dollars and involved tens of thousands of top-tier physicists, engineers, and technicians.

But Oppenheimer had a unique fate: after creating and leading the Los Alamos laboratory town for three years, where the bomb was physically constructed, he dared to question the American arms race strategy during the Cold War, especially regarding the hydrogen bomb. That was enough for his moral qualms, his political stances, and his open support for nuclear weapons proliferation control negotiations in McCarthyist America to bring him down from hero to suspect of colluding with the Soviet Union. From a national hero, he was excluded from accessing the most secret and sensitive information. He would be rehabilitated years later, only after a Senate committee clarified the instrumental nature of the charges against him. But in the meantime, he was humiliated: the American Prometheus, the one who stole atomic energy from the Gods to give it to mankind, underwent his torment.

The personal journey of Oppenheimer is well known and has been recounted in several biographies; it's a controversial story, full of light and shadow and, like the entire Manhattan Project, still a subject of discussion among historians of physics. I refrain from expressing an opinion on this matter. As an avid science viewer, however, I want to express an opinion on the film that English director Christopher Nolan recently adapted from Kay Bird and Martin Sherwin's Pulitzer Prize-winning 2006 book. Simply put: go see it! I believe it's destined to remain in film history, especially since it dares to tackle a historically relevant topic like the production and use of atomic devices, making it both archetypal and deeply human. The underlying themes echo thoughts from the "discovery" of fire: the ambition and frenzy of knowledge, harnessing natural power, using the resulting superpower, the struggle for control, and the anxieties of responsibility. Themes that resonate in Oppenheimer's contradictory personality, masterfully portrayed by the director and the actor who plays him, Cillian Murphy.

The film is divided into three parts, which – as always happens in Nolan's cinematography – don't unfold sequentially but in parallel. The three periods of the American physicist's life (from academic training in Europe, the introduction of quantum mechanics in the United States, building an advanced physics school in the USA, to the bomb; the indictment in '54; the rehabilitation by a Senate committee in '58) intertwine, and like in a thriller, slowly reveal the truth. Three hours of tension, of passion, in which we meet the physicist's life companions, his intellectual aspirations, his weaknesses, but also many key figures in the science of the past century, physicists who made it great, like Einstein, Born, Bohr, Heisenberg, Szilard, Fermi. In an unlikely twist, Nolan manages to immerse the general audience in the adventure of science and the resulting concerns, specifically those that led 20th-century physicists first to promote research on the military use of nuclear energy, to prevent the risk of Nazi technological dominance, and then to ask not to use that first bomb against Japan, or even to seek its absolute prohibition.

I must admit my admiration. Nolan, as a director and writer, manages to treat science's questions, even the most complex and hard-to-understand (like black holes or space-time paradoxes), making them accessible and engaging for all, in some cases even poetic, as in Interstellar. The most renowned actors are eager to star in his films, giving unforgettable performances, like in my opinion Robert Downey Jr.'s in Oppenheimer. And in this latest film, he manages to dignify the supposed naïveté of the ethics of responsibility, which confronts and challenges the scientific and technological hybris and the ruthless logic of the power struggle in a difficult, contradictory, non-linear dialectic with an uncertain outcome. The seventh art, cinematography, with Nolan, treats science and ethics on equal terms.

If we could find the same awareness in the protagonists of contemporary history, governments, and major tech companies, the dialogue on current issues - such as climate change and artificial intelligence - might be less trivial and more decisive.