In his recent article on Scienzainrete, Pier Mannuccio Mannucci mentioned it as a positive example. The Gruppo 2003 also cited it as a good practice in its Manifesto for a scientific research revival in Italy. What we're talking about is the evaluation system adopted by Telethon to fund research projects.

What it is, how it works and what results allows to achieve was explained by the Telethon Scientific Director, Francesca Pasinelli, on Friday 15 July in Turin, during the "It's their merit. The people that make…Telethon» event, held by the non-profit and high social utility organization (ONLUS) founded by Susanna Agnelli to present the overall results of the work that was carried out.

Telethon is a quality “charity”. Which has been raising funds since 1990 - as much as 27 million Euros in 2010 - to fund research projects on genetic diseases. What criteria does it use to evaluate these financed projects to be considered as an example?

It's simple. Telethon publishes a public notice of competition. And anyone wishing to participate can present a research project and have it financed if chosen. There is an international scientific and medical commission that judges ex ante all the projects, both those presented by external groups as well as those submitted by the Telethon institution groups. At the moment, the commission is made up of 28 members, only 3 of which are Italian (one working in Italy and the other two abroad). The reason for the scarce number of Italian Commissioners is to avoid any possible conflicts of interest.

Every project is evaluated by at least three commissioners, who are experts in a particular field. All projects are discussed in a specific plenary meeting. Each project is given a score. The best are funded.

Nothing new up to this point (even if it is all quite commendable): this is the same procedure that is being used by the National Institute of Health in the USA and is considered the best in the world. Because it rewards exclusively based on merit. Telethon has shown that this can be applied in Italy too.

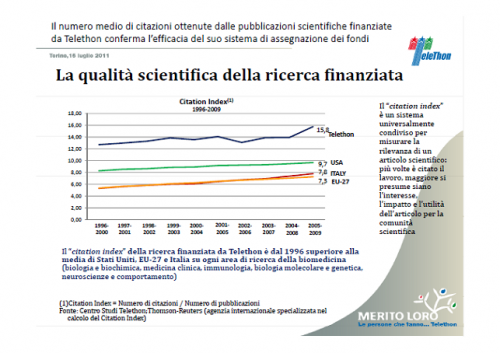

But does the fact that the system is the fairest also mean that the system is the most efficient? Data published by Francesca Pasinelli states it is. The number of citations (15.8) obtained on average by articles signed by the winners of the Telethon projects is, as seen in the diagram, steadily and significantly higher than the average number of citations received not only by articles written by colleagues working in Italy (7.8) and Europe (7.3), but also by articles written by colleagues working in the United States (9.7). Data processed by the Thomson Reuters experts shows that the Telethon authors receive more than twice as many citations received by Italian authors and 63% more citations received by American authors.

The ex ante evaluation system chosen by Telethon, therefore, is not only fair but it is also efficient. This is a system that could be taken into consideration even by the ANVUR, which could recommend it as a the ideal model for allocating public funds.